Blackface! |

Blackface History Prior to Minstrel ShowsCenturies before the first American minstrel put on the burnt cork mask, blackface was a familiar theatrical device in Europe. The most famous blackface performance in the legitimate theater is Shakespeare's Othello, first produced in 1604 and almost always performed by a White actor in blackface until nearly the end of the 20th Century. Verdi's operatic version will no doubt continue to be sung by blackfaced Whites until opera develops enough strong Black tenors to take over the role. As theater historian Robert Hornback explains, Shakespeare did not invent theatrical blackface, but was consciously using a convention with a very long tradition and some very specific implications for his audience. From the folk rituals of pagan Europe through Medieval religious pageants to the theater of Shakespeare's day, a black face and black skin were used to denote both evil and folly.

The symbolism was basic: white/light/day equaled good, dark/black/night equaled evil. Europeans simply carried the symbolism over to light and dark skin. A blackened, sooty or begrimed face was the sign of the scapegoat in pagan rituals. From the early Middle Ages, blackface, black masks, black gloves and leggings, frizzy-haired wigs and other devices made up the costumes of Satan, his fallen angels and the souls of the damned. Dark skin was also associated with the biblical mark of Cain (an association of which American minstrel men were well aware).

Feast of Fools festivities were often led by blackfaced or black-masked figures, the Lords of Misrule. The evil trickster Harlequin was routinely played in a black mask in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Morris Dance in rural England was led by a blackmasked fool, known variously as King Coffee, Old Sooty-Face or Dirty Bet. As late as 2005, every winter in the fishing village of

Padstow, in Cornwall, England, townsfolk were still blackening their faces and parading through the streets in festivities clearly descended from the Feast of Fools. Unfortunately, they called the event Darkie Day, leading to charges of racism and attempts to outlaw the centuries-old practice.

Charivari could often boil over into mob violence. Tarring and feathering, making someone

"ride the rail," the lynch mob and even the costumed vigilantism of the Ku Klux Klan can all be seen as extreme versions of charivari. Even stranger are the race riots that periodically broke out in the tenements and slums of lower Manhattan, when mobs of poor and discontent White youths ran wild in the streets. Their faces often blackened, they not only ransacked establishments symbolic of upper-class Whites, like the Park Theatre, but also targeted the homes, businesses and persons of their Black neighbors, producing the bizarre image of blackface-on-Black violence. Some of T. D. Rice's audience at the Bowery in 1832 had undoubtedly blackened their own faces and participated in this kind of street violence.

|

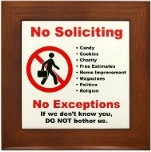

Buy a No

Soliciting Sign

That Really Works!

|

|

|||||

|

|

Visit the Blackface! YouTube Channel for more blackface and minstrel show videos |

||||

|

|

|||||

Racial and Racist Stereotypes in Media |

|||||

|

Blackface! Black Stereotypes |

Yellowface! Asian Stereotypes |

Brownface! Hispanic Stereotypes |

Redface! Indian Stereotypes |

Arabface! Arab Stereotypes |

Jewface! Jewish Stereotypes |

|

|

|||||

| Please visit our partners: |

| Buy * Will Write for Food * T-shirts |

| Kachina.us - Guide to Hopi Kachina Dolls |

| Agile Writer -- Biography and History |

Copyright ©

Ken Padgett